The Longest Game is an Occult Pulp Noir serial. To begin at the begin, or find your way around, see the Table of Contents.

Another front blew in from the Atlantic on a morning without coffee or toast. Calumn Quothe gathered the lapels of his raincoat about his neck, as misty ocean gales insisted on undressing him. Indecent behavior, even for the sea. Where the hell was she? Calumn tugged on his mustache as he groaned deep in his throat.

The Boardwalk of Glimsvale, Massachusetts was a hostile line of commerce ambling along a devastatingly sublime stretch of seaside. The whitewashed wooden planks had peeled under the drunken footfalls of alleged tourists. All of it wet without any rain. The silhouettes of the lighthouse and a derelict island just visible, despite the early hour.

Calumn paced the same few storefronts on the Boardwalk one more time, miming the actions of a lost tourist in case any potential onlookers out this early thought he was crazy. I’m lost! He tried to emote. Calumn did a shrug toward a closed t-shirt shop that he hoped said: But in a way that’s not my fault! Someone gave me bad directions! The two early-morning joggers might appreciate that.

What was happening to Calumn took a sort of nerve that you just didn’t find anymore. Old-hat gumption without the patina. As was habit, Calumn’s hand drifted to his baggy pocket for his memento, but instead heard the crunch of paper. He re-read the handwritten note for the fourth time, muttering himself a therapeutic “Ai-yuh-yai.” She had even signed it with a lipstick kiss, like a freak:

Dear Mister Quothe,

Don’t bother searching your pockets one more time-- your Archer is with me, safe and sound. Meet me before the sun rises, and I’ll prove to you I’m not crazy. Then you can have your plaything back. Boardwalk, sub. Walebone and Solace. Try and catch a few winks, handsome.

XOXO, Minerva

“This is what you get,” Calumn lectured to himself. “No ifs ands or buts. God it’s freezing, this is-- you get that too, mister.” The rain whipped his coat open again. Calumn hugged himself and patted his arms. “You get that too.”

He scanned the beach, hoping Minerva would show. He groaned, again.

Gimlet’s Gambit was a soft underbelly of passable barmanship under an impenetrable veneer of theming. Calumn could appreciate that, but his four-hour flight (one layover) was nearly for naught courtesy the bouncer. Themed bouncer. Some beefy all-in-black security-type was pretending to be a “street hustler,” in his folding chair hunched over a battered chessboard. The gated door beside him marked the bar’s entrance. Calumn’s contact had arranged their meeting at a chess club speakeasy. Charming, if not slightly compromised by the “hustler” scrolling on his phone.

A line of couples and cold, huddled friends waited for their turn in the opponent’s chair at the little table, so the bouncer could push a few pieces around and wait for a pretend password. Too tedious. Calumn moved to bypass the line for the gated door, and the bouncer raised an arm, blocking the way. “Get in line,” he muttered and turned to a woman with flappery chin-length hair just sitting down. “Knight to F-4.”

“That’s not even F-4,” Calumn cried as he watched a black bishop take a white rook at C-5. “-- that’s not even a knight!”

“Asshole,” decreed the bouncer.

The woman winked at Calumn. “The knight is young, and plans to join the clergy.”

“Ooh, that’s good. You’re cool.” The bouncer nodded to the door. “Knock twice, they’ll let you in. Doctor Watson here is gonna wait in the cold.”

“Oh, he’s not with me,” she said and sauntered inside. Noise poured out the door for a moment.

“Next,” the bouncer called. “Look man, don’t make my night hard. If you want in, just get to the back of the line, okay?”

Calumn shrugged. “Bet you twenty bucks I can take your king in a single move.”

“Bullshit.”

Calumn shook with his right hand, and grabbed the king with his left. “I’m lousy at chess, but I haven’t lost a game yet. Keep your twenty and let me through.” He tossed the black king to the bouncer.

The “hustler” laughed, actually slapping his knee. “Not bad, Doctor Watson. You’re still an asshole. Knock twice.”

The door led down to a claustrophobic cellar packed with folks, about half attempting to honor the dress code. A mirrored bar lit from beneath cast a hundred bottles of alcohol aglow like treasure, two painfully cool-looking bartenders moved glasses and shakers like a shell game. Across the bar were a row of chess-boards and their denizens.

“What are you having?” The woman from outside introduced herself with an over-familiar touch to his shoulder. He was squinting at a chalkboard cocktail menu, and turned to squint instead at her. Calumn quick-drew his glasses, plastering them to his face with two clumsy hands.

“Miss Calahan.”

“Minerva. Miss Calahan was my mother, and these days she’s too sober to be in a place like this.” Minerva fit into a themed speakeasy like gauze wings at a Renaissance Faire. Cocktail dress, a penciled eyebrow raised. Painfully plucky. “Quothe?”

“Like the raven,” he half-sang a jingle as he watched folks take to a music stage with a look of concern. He snapped out of it: “You asked something before, I’m sorry?”

“I said, ‘What are you having?’ She lifted hers for show. “Pistachio Tom Collins.” She even spoke with a Transatlantic drawl, dear God. Calumn had made a mistake. He stood in the crowd with its many elbows, voices fighting to beat the folks singing shanties in the corner.

“I’m having… doubts. I want to talk business, and-- is that an accordion?”

“This is Glimsvale, darling. We breathe shanties like New Orleans breathes jazz.”

“Do not invoke the name.” His native Louisiana would not allow the indignity of comparison.

Minerva punched his arm, like chums. “You’ll get by. We have a quiet corner-- that way, curtain booth” she pointed.

Calumn worked in both antiques and gaming; every client knew everything, was sure they were going to shake his foundation. He ordered a glass of red and resigned himself to another dead end.

At the hour mark Calumn sat at the pier and tugged on his canine to make sure this wasn’t a dream. The tooth held firm.1 He unpacked the note for a fifth time. Boardwalk, check. This was the boardwalk, seagulls and food grease and cold sand. It was almost as sinister as Coney Island.

Much of Calumn’s fears of Coney Island hatched from a childhood visit in which he believed the Steeplechase Face posed an immediate threat to his life. Sometimes, Quothe is not sure he is dreaming until the Sideshow Cat and Mr. Popadopolous are helping him hide and escape a giant floating Steeplechase Face trying to eat them. Even now, mouthful of teeth, he watched his back for a floating head.

Dreams never came with that pain in his chest Calumn now felt. “Ah,” like he was recognizing a vintage of wine. “A panic attack,” he ordained. Calumn put his back to a time-worn hot dog stand and tried his best to breathe. A shaking hand unpacked the note for a sixth time. Walebone and Solace. Check. The two streets converged to the right of the hotdog stand, this long stretch of boardwalk being Walebone Way and Solace Street the brick alleyway of shops that wound up the streets to Glimsvale proper.

He groaned and slid down the stand until his butt hit the pavement. In a few minutes he would head up Solace, take a streetcar to the edge of town, and head back to New Orleans. He would invent some semblance of life without the Archer. For now, he could wait until the sunrise, in case Minerva showed.

Calumn parted the scarlet fabric of the curtained booth with a gentle karate chop and balanced his wine on the table. She sat there, handbag on the table and otherwise encumbered by nothing.

Calumn pulled out a notebook and pen, which he clicked twice. “Okay. Shoot.”

“You know, I thought you’d be older. Antique scholar, or what you call it--” she put a business card on the table. It read: ANTIQUE GAME RESTORATION AND RESEARCH SPECIALIST.

Calumn head tilted his head. “That’s how you found me?” He picked it up and checked both sides. Embossed black lettering nestled betwixt the images of a knight-- not his personal choice of chessman. The horse heads were tiny, like special characters on a typewriter. That was his name, though. His phone number, his job title. Except-- “I’ve never had a card like this. I don’t do cards.”

Minerva raised an eyebrow. “Then someone went through a whole lot of trouble to make me this nice card for you. Mighty kind, wouldn’t you say? If you’re the man for the job.”

“Job?” Calumn held the base of the wineglass like a planchette, rotating it in circles, gently stirring his wine. “I believe you’re the one who had some information for me.”

“There’s a game, in old town Glimsvale. Hard to find.”

“What’s it called?”

Minerva shrugged. “It’s funny. My… associate, he told me the game has no name. But he was also insistent it has three names. Oh, gambit-something. Something to do with gambits.”

Calumn brought the glass to his lips, but waited to drink. “Have you seen the board?”

“I have, actually. I planned to take you there tonight-- that is, if you’re interested.”

Ah. Coy. “Gambits, indeed.” Calumn allowed himself a sip. “Peppery.”

“I think I’ll take the pistachio to pepper. So here’s the part where this takes a strange turn, Mr. Quothe.”

Quothe gave a tight smile, unseen under his mustache. He clicked his pen twice.

“This game. My associate says that beating it can grant you your heart’s one true desire.”

“Right. People get weird like that about a lot of games— chess, go. Parcheesi.” Quothe sipped his wine, the empty page of his notebook keeping track of all he found unnoteworthy.

“Not like that. Actually, Mr. Quothe. It grants you a wish, if you can win.”

Calumn’s heart sunk and twisted, it might have tumbled out of his mouth and splashed into his wine, if he hadn’t swallowed. “Ah,” he ventured. “Interesting philosophy. Why don’t two people wish for a million bucks and then split the profits whoever wins?”

“Because you play against a clockwork man.” Minerva’s voice cracked.

“Oh, so it’s the Turk all over again.”

“He’s called something like that! The Turk or something gauche. Maybe you two know each other?”

“Yes.2 The Turk was a hoax. Which makes you either a rube or a con. I prefer not to suffer either-- Goddamn it!” He swatted the table. “I’m talking like you now. Look, you told me you knew what game this belonged to.”

Calumn pulled from his raincoat a blue silk handkerchief, emblazoned with stars. Wineglass still in his right, he unwrapped the bundle in his left-- upon the table, his Archer. A mahogany chessman of sorts, with warm-colored gilded rings about the column. An elegant crescent moon atop, shot through with an arrow of that same delicate metal. Minerva’s eyes fixed on the piece.

“Now. I don’t care if this game can cure cancer, improve someone’s golf game, get another season of cancelled show. Great. You say you’ve seen the game. You brought me here because you said the Archer belongs to it. But that can’t be true. Is it?”

“I need to play, and I need to win,” Minerva plead. “What’s your day job, you what, read game manuals? Nobody knows the rules, that’s what he told me. You could learn the rules, and teach me.”

Why did he do this to himself? Nothing good ever happened on the east coast. Calumn took a long, angry swing of wine. “Does the Archer belong to the game or not.”

“That’s the best part,” Minerva leaned forward. “Once you put it on the board, it belongs fair and square.”

“This is-- if you’ll excuse me-- a criminal waste of my time. You’re lucky I spend my days reading game manuals, and not the law, or maybe I’d know with what precise crimes you wasted my time with.”

“Please,” she crooned.

“Look lady, I flew across the country on what I thought was a good lead. A damn good lead. Not a robot genie--”

“Magic is real,” she seethed. “The Midwayman showed me, and it’s real. Please.”

Ah. “Obviously you’re disturbed. I’ll leave you to that-- respectfully, of course.” He folded the silk back over the Archer, beyond the desperate stare of Minerva. “Best of luck with this whole thing you’ve got going on.”

“Please. You can’t, you--” as she began to cry, reaching for Calumn’s sleeve, she knocked his wine glass, spilling onto his sweater. “OhmygodImsosorry--”

Calun held his hands up, yanking off his raincoat and tumbling out the booth. “Napkin!” he yelled, like he was calling for a medic. “Napkin? Napkin!” He took one more look into the booth to say something as venomous as he felt, until he saw Minerva, head in her arms, crying into the table. He ran to the bathroom, murmuring a comforting “there, there,” well out of her earshot and mostly for himself.

Minerva had left by the time he returned. Calumn could hardly blame her, embarrassed as she must be. He grabbed his coat, and palmed his wrapped blue handkerchief. Once outside the bar, he decided he rather liked the accordion music, after all. At the very least, he would have a story to tell, back home.

It was only after the streetcar back to his hotel he found that inside the blue silk handkerchief was a folded ransom note and a tube of lipstick. The story was far from over.

“Sun’s rising,” he told himself. A lavender line now severed the ocean from the sky. Minerva wasn’t coming, and she had taken the Archer after all. “I followed the note to the letter! Come on!” Calumn kicked a grassy sand clump and stomped the boards beneath him in two angry hops. Who didn’t show up to their own ransom terms? Calumn would have his revenge. He would have justice. He could call the police. That’s what he would do-- this was the exact sort of thing calling the police was for. He dialed 911.

“Hello? Hi, yes hi-- I’d like to report a stolen object?” Calumn now paced with purpose. Speaking on the phone meant he had every right to be walking anywhere.

“Right. It’s sort of a, we think it’s a-- I personally think it’s a chess piece.” Calumn abandoned Walebone and Solace, power-walking through the alleyways of closed bars and tee-shirt shops. He scanned the windows, half expecting to find Minerva peeking from behind glass.

“I’m sure it was stolen, because the thief wrote a note admitting they took it. I have the note right here! She kissed it and everything.” He triumphantly waved the note for nobody. Calumn picked up the pace as the sky turned pink. People like Minerva vanished in the daylight, and he was impatient for the dispatcher to send someone.

“I don’t know where she lives, no. I met her last night. No, no. Gosh, no, but-- no, I didn’t lose it. I can’t replace it. It’s very valuable.”

Calumn now was walking up a narrow corridor between a pizza shop and the double-glass doors of an arcade.3 “I’m near Solace Street. There’s a pizza place called-- well it just says ‘Pizza’ to be honest. The pizza slice is shaped like Italy? So maybe Pizza Italy or--”

Impossibly, Minerva was staring up from the ground, and Calumn almost stepped on her face. The Italy slice pointed to her like the finger of --

“God.” Calumn hung up the phone and knelt to her side. She had been opened like a purse from neck to abdomen, blackened blood soaked into her clothes. Same dress and heels as the night before, though she’d added a baseball hat and overlarge varsity coat. One eyebrow was still raised, quizzically challenging.

The blood had been painted along the pavement up from where her head lay and down from where it pooled at her back to below her feet, forming a phi4. These extremities of blood marked the top and bottom of a gory circle about the body. Minerva lay there, her insides scrambled in the great wound like soup in a bowl. There were objects scattered upon the circle of blood, but Calumn’s vision was obscured by tears, his mouth flooding with the saliva that comes before vomit.

You may continue reading to Chapter 2: I Miss la Croc & His Birdo Me, or navigate the Table of Contents.

AURIBELLO:

If I am wakeful, wakeful skin shall smart,

So pull upon my toothsome grin, this art

Is one hatch’d not without a clever jest;

A fist of marbl’d berries fail the test.

-- “The Dreamer of Autua,” (Act 2, Scene 4)

The Turk, 1770. Wolfgang von Kempelen. A Hungarian inventor and grifter whose bid for clout involved a chess-playing automaton. Thing was, it was operated by a sweaty contortionist who puppeteered the Turk against such opponents as Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon. Kempelen died before his ruse was discovered. An army of clockwork foreigners and devils would follow. Some of them would be real, particularly after the invention of computers.

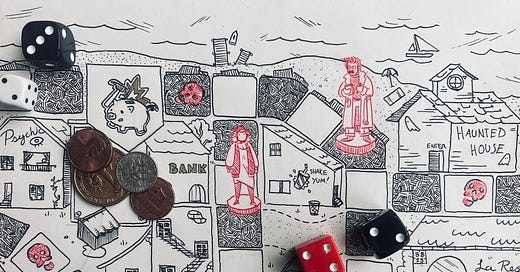

There is no “Tourney Tops!” or “Carir Mode” in this arcade, and certainly its patrons are not graced by the Byzantine. The main entrance facing Solace Street designates this as the Argh-cade, one of countless shallow pirate-themes which end at the door. There are six rows of ski-ball and a cannon game where players shoot rubber balls at a giant smiling clown face. The Elevator Action here has been out of order for years but a pink sheet of construction paper taped to the screen places it for sale. A child named Daniel Richards is afraid next summer the machine will be gone, and it will be. At $250, the game box was underpriced but beyond the liquid assets of a child. The Byzantine is not here, but it is close enough. After the Warlock makes a complex move, he lingers a moment before letting go of his pawn and relenting his turn.

Φ